Rattan Made New—Part I

Our characterful homes are designed and inspired by our community of homegrown creatives, and you’ll find some of our conversations and musings here on the Figment Journal. Perhaps there’ll be a lesson or idea to bring into your own home!

To start us off, architect Lingxiu Chong shares a three-part exploration of rattan and its continual reinvention today.

Rattan is an intriguing material and motif in design history to think about. In no small part because it is a material we recognise and regard as traditional, local and ‘ours’ – they feature in many of our childhood memories of elderly relatives’ homes and various other spaces in our tropical island city. I am continually drawn to rattan objects—furniture, blinds, baskets and boxes, lampshades and more—for sentimental reasons, but also in my training as a designer, I find myself critically appraising the role and issues it raises in modern design history and material culture.

While to most people the appeal of rattan lies in its natural origin and nostalgic quality, I prefer to think of it as a thoroughly modern, hybrid material par excellence. It is simultaneously a material that’s used widely in many indigenous craft traditions, still worked with by hand but also mass produced in sheets as an industrial product and replicated in plastic. Call it by its other names — wicker, cane, reed — and you’ll find it at home in New Orleans, Egypt and other far flung destinations, hailed as the definitive texture of that place and aesthetic. What’s more modern than to be at home anywhere in the world?

A museum installation by Japanese contemporary bamboo master Tanabe Chikuunsai IV / Tai Modern

Rattan art objects, handmade in Malawi / As’Art Gallery

A room fully furnished in rattan, styled by Atelier Vime in Provence / Atelier Vime

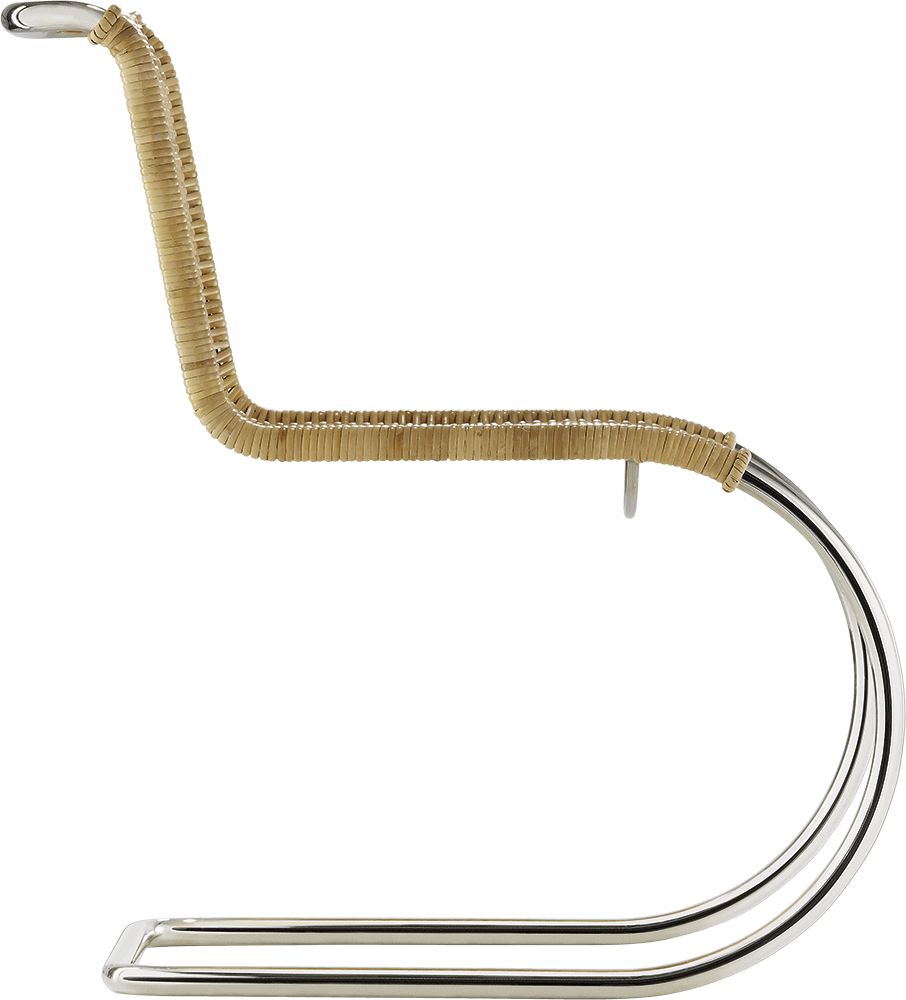

In particular I find how early modernist designers approached rattan to be instructive. The objects they created reflect this moment of transition and hybridity in industrial production processes in the early 20th century. The ‘Cesca’ Chair by Marcel Breuer began a lineage of household furniture that pairs rattan with industrial materials such as bent metal tubing. The chair, produced by the Thonet company in Vienna, Austria, was made of chrome-plated tubular steel, wood, and hand-caning. Soon after, his student Mies van der Rohe created the B42 chair that evoked even greater lightness and elegance in its form. Around the same time in the 1920s, Charlotte Perriand, a bold young female designer in her 20s, created the first version of the now iconic LC9 stool for her own dining room in her Paris apartment, made of tubular steel with a rattan seat.

The ‘Cesca’ Chair by Marcel Breuer / MoMA Collections

The B42 Chair by Mies van der Rohe / Tecta

The LC9 Stool re-issue / Cassina

The juxtaposition is striking – part mechanical, part craft, both honest in its construction and more related in spirit than not. Each serves its respective functions and work together to support the weight of the seated person with a slight spring. Perriand was prescient in her choice of rattan as the ‘traditional’ material to pair with steel, the defining material of the machine age, to enter and become assimilated into the domestic sphere.

In this way rattan lent itself to explorations of different kinds of aesthetics and identities. It also embodied issues of cultural perception and identity. The Japanese-American designer Isamu Noguchi created a piece in rattan in collaboration with modern-minded Japanese designer Isamu Kenmochi, and the story of this object reflects both designer’s exploration of how to reconcile traditional and modern ideas.

A photograph of Isamu Noguchi and Isamu Kenmochi seated together on the prototype chair they collaborated on / Michio Noguchi and the New York Times

The design, recreated from photos of the lost prototype / M+ Museum Collections

A detail of Isamu Kenmochi’s rattan furnitures / WA Design Gallery

Isamu Noguchi’s 1957 sculpture, Calligraphics / Noguchi Museum

Isamu Kenmochi embraced the Western concept of a chair, then considered alien and suspect in postwar Japan, to create what he termed ‘Japanese modern furniture’, seating designs that gradually made their way into everyday settings in Japanese homes, restaurants and public buildings. Again, rattan serves as an instrument for bold new ideas about domestic objects for modern life. As for Noguchi, working with rattan was one touchpoint in his complicated and lifelong negotiation with his Japanese identity. The recreated prototype that we see is crude and entirely made by hand: both the partially basket-woven seat and backrest, as well as the legs formed of a single slender iron rod. In this case, the combination of rattan and metal reflects a negotiation between traditional craft and habits and cosmopolitan modernity. My favourite quote from Noguchi is, ‘To be hybrid is to anticipate the future’.

The history of rattan objects also raises questions of authorship and the resulting perception of value. Take the now iconic “Jeanneret chair” and the collection of teak and rattan furnitures he designed for the modernist Indian city of Chandigarh, planned by his cousin Le Corbusier in collaboration with British architects Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew.

A photograph of abandoned chairs from Chandigarh’s civic buildings / Dimo Studio

A set of 5 vintage library chairs originally made for the Chandigarh public library with recently restored caning / Dimo Studio

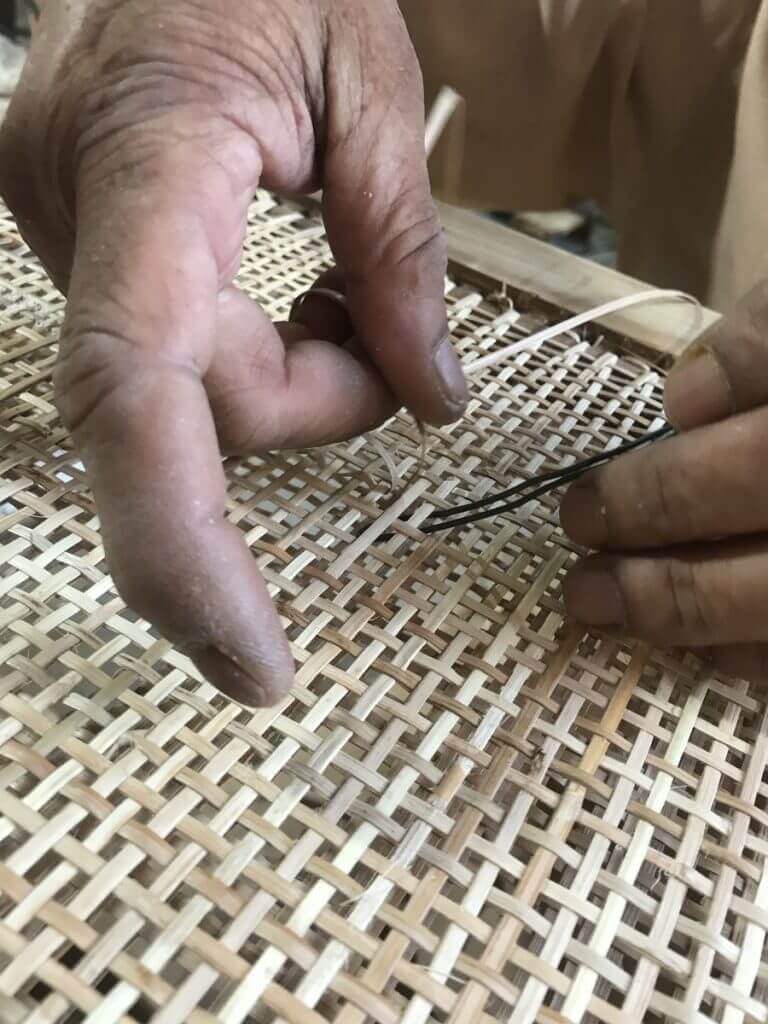

A close-up of Dimo’s caning artisans at work / Dimo Studio

A table setting in the Kanaal complex designed by Axel Vervoodt / Jan Liégeois for Surface Magazine

It’s fascinating how the perceived value of these objects changed over the decades, from the public library to the trash heap and then to the auction house. Designed to complement a bold and expansive vision for a model city of post-independence India, these furniture were designed to be robust and practical, crafted by local craftsmen in familiar materials: iron rod, rope, rattan, teak. They were installed across numerous municipal buildings, intended for everyone’s use. Yet over time as the city deteriorated, the furniture was discarded en masse and even repurposed as fuel. Doesn’t it feel somehow to the credit of the understated design and craftsmanship, to be so in keeping with the local vernacular as to be treated so humbly? It has only been due to renewed attention from foreign designers and historians to his legacy that there are new efforts to restore and reproduce these chairs, even in collaboration with some of the original carpenters (it would seem that craftsmen will have the final word after all.)

In the hands of talented craftsmen and designers with an eye to the future, the interpretation and use of rattan becomes more layered and thoughtful each time. We will continue to explore this topic with other creatives with their own unique takes on the material and how to balance tradition with modernity.

Lingxiu Chong is a Singaporean architectural designer and conservator currently based in San Francisco.

If you’re a fan of rattan, read about our very own Shang House, inspired by the history of rattan manufacturing in its Balestier Conservation Area neighbourhood.

Comments